The History of Reading

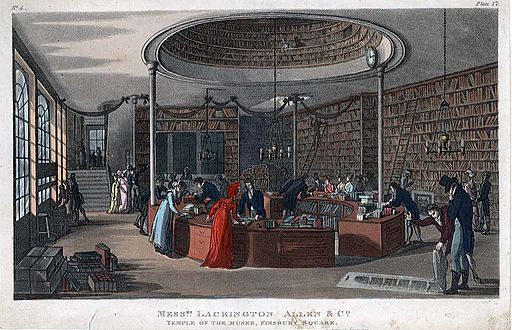

In the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, reading was a privileged skill available to the upper-class elite. Books were very expensive items and most of the population were unable to afford them. One of the more famous and prestige bookshops of the period was 'The Temple of Muses', situated in Finsbury Square, London. Founded by James Lackington in 1778, the architecturally stunning store had a frontage of 140 feet and the premise was so large that it was reported a coach and six would be able to drive around the huge circular counter in the centre of the shop. Lackington later sold the bookshop to Jones and Company where it continued to thrive, selling books at the lowest possible rates whilst maintaining an attractive and prosperous space for individuals to read and browse the latest texts. The Temple of Muses burnt down in 1841.

In the early nineteenth century, it was very common for individuals to be able to read but not be able to write, although these statistics are likely influenced by economic factors as well as capability: paper was expensive, and writing with a quill time consuming and difficult, and therefore not that common. However, most illiterates had had contact with at least one literate person, which meant that to experience a text you do not have to read it. Newspapers were read out loud in public houses and Dickens's serialised novels were commonly read aloud in the home by a literate family member.

In the 1830s and 1840s a new form of printed text emerged: a lengthy prose fiction serialised in one-penny or twopenny weekly parts. These were usually stories involving adventure or Gothic-like elements. Many had no planned, pre-written end; they just continued until the public were no longer interested in the story. Some penny weekly novels in the 1850s and 1860s were serialized over four or more years. Increased production of this sort could only be supported by an increasingly literate population.

In 1870 the Education Act (sometimes called the Forster Education Act) was introduced by parliament. Drafted by W. E. Forster, the act campaigned for free, compulsory and non-religious education for all children, and helped to establish the foundation for generalised literacy rates across England in the late-Victorian era.

The Novel and Serialised Fiction

Most Victorian novels were published in three volumes called the triple-decker or three-volume novel at 31s. 6d, or 10s. 6d per volume. This price, although too expensive for the average purchaser, enabled the publisher to cover their costs whilst allowing for a reasonable payment to go to the author. Those who could not afford to buy new novels used the circulating libraries newly established across the country. A novel divided into three parts could create demand, and the income from the first part could also be used to pay for the printing costs of the later parts. Furthermore, as most individuals obtained their books from the circulating libraries, the librarian at these premises had three volumes bringing in money, rather than one. The particular style of mid-Victorian fiction - a complicated plot reaching its conclusion through marriage and the acquisition of property - was well adapted to the form.

One of the more famous of the circulating libraries was the Mudie's Lending Library and Mudie's Subscription Library established in London by Charles Edward Mudie from 1852. The lending libraries such as 'Mudie's' had a strong influence over publishers and authors as they were able to reach a much larger section of the reading public. Such was the strength of Mudie's influence that he was also crucial in the success of scientific volumes, purchasing 500 copies of the first publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. The decline of Mudie's eventually came as a result of the rising number of government-funded public libraries, which were much cheaper and accessible to a wider range of the population.

Authors and publishers were anxious to increase their sales by reducing the price of new fiction. Dickens was one of a number of authors who tried to break through the rigid system of the three-decker novel. Using the idea of the lower-class form of the weekly-part novel as a model, he started to publish his fiction on a monthly basis at a shilling per instalment. Unlike the previous serialised fiction, there was a limited number of twenty parts serialised over nineteen months (the final part was a double issue at two shillings). Up to this point book sales had been small. However, the advent of serialised fiction popularised by Dickens's work meant that at the end of the nineteen months, the reader had an entire novel for a pound rather than thirty-one shillings and sixpence.

Novels issued in several monthly parts were framed by advertisements for a variety of items pitched towards the middle-class reader. They were surrounded by news reports, critical articles, and the latest reviews. This meant that for Victorian readers, the novel was not a self-contained entity but rather a text surrounded by a material framework of various fonts and images, which created a different reading process when reading the novel as we would encounter when reading a work of fiction today.

In 1849 the publishing house Routledge started the first Railway Library. The books were cheap, priced at one shilling per volume, and designed to be read whilst traveling by train. The library proved to be a great success because railway carriages were lit and, unlike when traveling in a horse-drawn vehicle, the ride was steady enough to read without becoming ill. This made train journeys the ideal environment in which to encourage reading and promote fiction. These perpetuating effects are evident in the success of the Railway Library venture; by the time it came to an end in 1898, it had published 1277 volumes.

Once a serial had been completed, it was often reprinted in a cheaper (usually 6 shilling) one-volume edition, and then again as a yellowback available in the Railway Libraries. The second-half of the nineteenth century saw the 6 shilling novel emerge as the preferred form for publishing new fiction. Faced with the growth of free, government-funded libraries, the circulating libraries decided to take necessary action in an attempt to ensure their continuation. In 1894 they announced that they would pay no more than 4 shillings a volume for fiction – a declaration that signaled the beginning of the end for the pricey three-decker novel.

By the end of the nineteenth-century, railway travel, circulating libraries, and affordable serialised fiction had brought books within the reach of many members of the newly-literate working-class population, who had previously been excluded from the world of the book.

Illustration

The history of nineteenth-century printing is tightly interwoven with that of illustration. Many serialised novels were accompanied by illustrations depicting scenes from the text, ranging from full double-page images in illustrated newspapers such as The Graphic to tiny vignettes enclosing the first letter of the opening chapter in periodicals such as The Cornhill.

The expansion of literacy in the early-nineteenth century was associated with pictures since learning the letters of the alphabet involved pictorial prompts. Illustration was incredibly popular and common place: Dickens' publications were accompanied with drawings by Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne) or George Cruikshank, and ten of Thomas Hardy's novels were first serialised with accompanying illustrations in magazines or newspapers. Poetry collections were also printed with detailed images included in the pages: the Moxon edition of Tennyson's Poems (1857) was a fully-illustrated collection of the poet's works, drawn by several pre-Raphaelite artists including Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

The engraved boxwood block was the most significant piece of technology which dominated early Victorian book illustration. The illustrations used to accompany prestigious fiction by such authors as Dickens and Hardy were of the highest quality, made from wood engravings painstakingly crafted by engravers from the artist's original design. Eric de Maré acknowledges the splendour and success of the wood-block industry of the nineteenth century in the following quotation:

'When these publications were illustrated, as so many were, the wood-block was the only means – helped by the metal stereo and electrotype, by which pictures could be printed with text in a single pressing on the same page. It required the growth of a great craft industry, the finest of the century'.[1]

The above remark identifies the wood-block as being the most significant mode of production behind Victorian illustration. De Maré explains how the technological advancement of the wood-block enabled the image to be printed on the same page as the text. This development simplified the reading experience and enhanced the correlation between word and image, thereby aiding the popularisation of illustration and its use in periodicals. Even those who were illiterate or semi-literate could gain immediate access to the fiction via the visual image without having to read the printed text.

The high standard of illustrations used by publications such as The Graphic and The Cornhill stem from the consistent use of classically trained artists, who were able to produce quality work which helped popularise illustration and increase demand for images. The quality of these illustrations and a confidence in their prestigious nature is exemplified in the serialisation of Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles in The Graphic. Four artists were employed to work on the different illustrations at significant cost, including the famous Hubert von Herkomer, whom the other three artists trained under.

References

- Eric de Maré,The Victorian Wood-Block Illustrators (London: G. Fraser, 1980) p. 7.