This essay is the third of four distilled from a lecture series on Aphra Behn given by Dr. Abigail Williams of the University of Oxford and adapted for the Great Writers Inspire project by Kate O'Connor.

Aphra Behn and Political Culture

1684 Frontispiece to Behn's Love Letters Between a Noble Man and His Sister [Public Domain],via Wikimedia Commons

Like her male competitors (John Dryden, Thomas Shadwell and John Crowne), Behn produced highly political stage plays that were firmly entrenched in the topical issues of the time. She also produced poems on affairs of state, in the form of panegyrics to Charles II and James II and their queens, and to public figures such as the fiercely Tory government censor Sir Roger L'Estrange. Her prose fiction was highly political. In particular, Love Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister is a very partisan account of the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685, refracted through the perspective of French erotic romance.

Most of Behn's political writing was written in the last decade of her life, in the years between 1678-89. These were years of great political upheaval, covering the Exclusion Crisis, the formation of the first recognisable political parties, the arrival of William of Orange at Torbay in November 1688, and the 'Glorious Revolution'. One of the most striking aspects of the literature of the 1680s is its engagement with the issues generated by these events. This is the period that saw the birth of party-political literature. Over the course of the decade, the press, which had been liberated by the lapse of the licensing act in 1679, pumped out thousands of pamphlets, poems and newssheets as Whigs and Tories, Anglicans and Dissenters tried to justify their political and religious positions in a rapidly polarising print culture.

Exclusion Crisis

The Popish Plot, and the Exclusion Crisis that followed it, were started with a rumour. In October 1678 the Privy Council began investigating the fictional allegations of Titus Oates, a discredited Jesuit novice, who had claimed that he knew of a popish plot to assassinate the king. His tale was given credibility by the sudden murder of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey, the judge to whom he had made his depositions about the plot, and it was immediately assumed that the murder was the work of papists. This fear of Catholic conspiracy was increased by the discovery that the seized papers of Edward Coleman, the Duke of York's former secretary, contained treasonable letters to Louis XIV's confessors about a plot to overthrow the Church of England and re-establish Catholicism as the national faith.

One of the 1849 series of Playing Cards Depicting Aspects of The Popish Plot [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The apparent confirmation of the plot aroused concern about the future safety of the Protestant religion, concerns which had been growing over the course of the 1670s. Fears were focused on the political and religious implications of the eventual succession of Charles II's brother and heir, James, Duke of York, whose Catholicism had been evident since 1673, and who was married to a Catholic Italian princess, Mary of Modena. Out of the hysteria over the Catholic threat a pressure group emerged, who believed that the only way to safeguard the national religion was to pass a Bill of Exclusion to prevent James from ever acceding to the throne. This group was soon to be known as the Whigs, a name derived from 'Whiggamores', fanatical Scottish Puritans, while those who opposed them became known as the 'Tories', from a name for Irish brigands.

Images of Party

One of the most confusing aspects of the literature of the Exclusion Crisis is that many writers were anxious to distance themselves from affiliation with either Whig or Tory parties. In this period it is rare to find either Whig or Tory writers describing themselves as such. Because Whig and Tory were initially terms of abuse, and because the party-political system had not yet solidified in the political imagination, Tory writers would write disparagingly of 'Whigs', but they would not necessarily use the term 'Tory' approvingly of themselves. Authors from both sides often presented themselves as moderates who were steering a careful middle way through the troubled waters of political partisanship.

Writers showed that they were transcending party allegiance by presenting party politics as factionalism, so that their own political agenda appeared to be neutral. This makes it difficult to pin down a particular writer's political allegiances. In the prologue to The Feign'd Courtizans, Behn laments the extent of public preoccupation with affairs of state:

'The devil take this cursed plotting Age,

'T has ruin'd all our Plots upon the Stage;

Suspicions, New Elections, Jealousies,

Fresh Informations, New discoveries,

Do so employ the busie fearful Town,

Our honest calling here is useless grown;

Each fool turns Politician now, and wears

A formal face, and talks of State-affairs…'

Yet this is in the context of a play that was dedicated to Charles II's mistress Nell Gwynn, a dedication which gave clear signs of the way in which Behn was aligning herself in the rapidly polarising London of the late 1670s. She continued to be profoundly engaged with the issues arising from the Exclusion Crisis, and unswerving in her conviction that the Whig Exclusionists were out to bring down the monarchy and society with their lawless, self-interested, and demotic political agenda. Over the next five years, she would join John Crowne and John Dryden in their concern to fight and win the battles of Whitehall on the boards of Drury Lane.

Although both Whig and Tory writers were quick to draw on a thriving tradition of anti-Catholic rhetoric in response to the Plot, they were more commonly divided by their differing interpretations of the religious implications of the crisis. On the whole, loyalist Tories like Behn saw the threat to national stability as coming from the assault of dissenters on the Anglican Church and the monarchy. Whig Exclusionists, on the other hand, many of whom were dissenters, were worried about the harsh laws against religious nonconformists, and the royal encouragement of Catholicism, which was believed to come hand in hand with political absolutism.

Tory writers like Behn attacked the Whig opposition by stressing its commitment to radical religion, and emphasising its links with republicanism. Many of the First Whigs had either been republicans, or had come from families that had supported Cromwell, and so their opponents suggested that what they really aimed at was a rerun of the events of the 1640s and 50s.

From as early as 1678, Behn linked Dissent with political sedition. The title character of Sir Patient Fancy, a Dissenting Whig alderman, is described as 'vainly proud of his rebellious opinion, for his Religion means nothing but that'. Behn approves of true Protestantism, in the form of Anglicanism, which in the Royalist Sir Anthony in The City Heiress, is defined as 'good wholesome Doctrine, that teaches Obedience to the King and Superiors, without railing at Government, and quoting Scripture for Sedition, Mutiny, and Rebellion'.

In The Roundheads, Loveless claims that all Puritan women are 'sanctify'd Jilts…make love to 'em, they answer in Scripture'. This sanctifying religion was pure hypocrisy, a language used by knaves in the pulpit to 'brew Treason' in the rabble. When the insipid Lord Fleetwood speaks in the Puritan language of the godly, Lady Lambert is infuriated. Whitlock patiently explains 'Madam, this is the Cant we must delude the nation with' and Lady Lambert angrily replies, 'Then let him use it there, my Lord, not amongst us, who so well understand one another'.

Here Behn establishes a principle that was to inform her later fiction. Godly cant is simply a means of deception, and Whigs are marked by their use of rhetoric to deceive. Tories, on the other hand, 'understand one another' without wrapping their devious intentions up in the language of religious zeal. We see this politicized emphasis on language as deception in the Love Letters: it is Philander, the Whig rebel who teaches the Tory Silvia the persuasive power of 'the Rhetorick of Love'. As she says, 'how do they not perswade, how do they not charm and conquer; 'twas this with these soft easie Arts, that Silvia was first won'.

As the novel progresses, we of course become increasingly mistrustful of the 'Rhetorick of Love', as the combination of epistolary form and narratorial intervention enables us to see the way in which both Philander and Sylvia use language as their own form of romantic cant. In the very first letter, Philander attempts to sway Silvia in terms which clearly mirror Whig political rhetoric:

'Your beauty shou’d [...] force all obligations, all laws, all tyes even of Natures self: You my lovely Maid, were not born to be obtain'd by the dull methods of ordinary loving; and 'tis in vain to prescribe me measures; and oh much more in vain to urge the nearness of our Relation. What Kin my charming Silvia are you to me? No tyes of blood forbid my Passion; and what's a Ceremony impos'd on man by custome?'

In this passage, Philander uses rhetorical casuistry to undermine the absolutes of law and custom that were so central to the ways in which Behn and other Tories viewed the political order. It was obligations, ceremony, and custom that were at the heart of the monarchical government that they saw as under threat from Whig fanatics. Philander's spurious arguments against these social, religious and political norms thus mirror what behn sees as the devious and ill founded claims put forward by contemporary Whig polemicists.

Politics in the City and City Comedies

Linked with Behn's assault on the linguistic dissimulation of Whigs and dissenters are her class-based attacks on the London city-merchants and aldermen who made up a large part of the Whigs' support. These city types, or 'cits' as they are commonly referred to in the drama and satire of the time, tended to be Whigs for a mixture of religious and economic reasons. Many of them were Dissenters, from traditonally Puritan families.

The city of London became the focus for the political battle that was dividing the country, both in terms of municipal politics, and its representation in imaginative literature. There were debates between Whigs and Tories over the validity of city politics – London was the home of one tenth of the national population, and of the most easily mobilised body of popular support. It was here that the Whigs organised their petitions and pope burnings, and here that the Tories saw the most visible signs of the populist politics that they feared so much.

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 2nd Earl of

Shaftesbury (1652-1699). One of the Whigs that inspired Behn's Sir Timothy Treat-All [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Out of the turmoil of municipal politics came a spate of Tory comedies, such as Aphra Behn's The City Heiress(1682), parodying the archetypal prosperous City Whig. Behn's satire centres on Sir Timothy Treat-all, a hypocritical Whig Dissenter who is a composite of The Earl of Shaftesbury, Sir Patience Ward, the Whig Lord Mayor, and Sir Thomas Player, an old and notoriously lecherous City alderman. From the beginning of the play, Behn foregrounds Sir Timothy's greed and lack of political integrity, as he declares:

'My Integrity has been known ever since Forty-One; I bought three thousand a year in Bishops Land, as 'tis well known, and lost it at the Kings return; for which I’m honour'd by the City'.

Sir Timothy treat-all was a type of lecherous cit who was to recur throughout Behn's drama, as Sir Patient Fancy in Sir Patient Fancy, Francisco in The False Count and Sir Feeble in The Lucky Chance. The type can be found elsewhere in Tory drama, most famously in Thomas Otway's Venice Preserv'd, where the elderly senator Antonio's craven lechery is made comic in a scene where he persuades his mistress to kick him and spit at him while he pretends to be a dog.

For Behn, the elderly city fool provided both an endless source of sexual intrigue, as young virgins attempted to escape their elderly admirers to be with their true young partners, and a way of questioning the economic roots of arranged marriages. It also offered a way of inflecting her comedy with political nuances, as the old and covetous city politician was offset against her young and virile cavaliers.

The critique of Whiggish associations with the city can also be found in Behn's poetry. In other Tory writing of this period, anti-Whig satire frequently took the form of a critique not just of individual city aldermen, but also of the whole culture of trade that supported them. Although writers once celebrated the affluence brought by the port of London as a sign of the country's well being after the Restoration, by the 1680s it had become a corrupting evil.

Behn's verse incorporates this attack on trade, particularly through her representations of the Golden Age. Behn idealised the past and represented it as the opposite of all that was most detestable in modern life. In the golden age, a world of ease, plenty and free love was offset against the world of commerce, money, and trade:

'Right and Property were words since made,

When Power taught Mankind to invade:

When Pride and Avarice became a Trade;

Carried on by Discord, noise and wars,

For which they barter'd wounds and scarrs;

And to Inhaunce the Marchandize, miscall'd it Fame'.

Along with many other Tory writers, Behn linked the religious nonconformity and trading interests of her opponents to create a stereotype of the Whig as hypocritical, prudish, and covetous, with a provincial narrow-mindedness that she despised. So in 'The Golden Age' the images of sexual licence and freedom that she invokes are part of a wider cultural distinction between a Tory/aristocratic/libertinism, and self-serving Whig propriety. Thus the commodification of female sexuality has a party-political resonance. 'Honour', as she sees it, is a concept designed to police and control desire through the restrictive social codes associated with Dissenters and Puritans:

'Thou Miser Honour hord'st the sacred store,

And starv'st thyself to keep thy Votarie poor.

Honour! That put'st our words that should be free,

Into a set formality.

Thou base Debaucher of the generous heart,

That teachest all our Looks and Actions Art;

What Love design'd a sacred Gift,

What Nature made to be possest,

Mistaken Honour, made a Theft,

For Glorious Love should be confest:

For when confin'd, all the poor Lover gains,

Is broken Sighs, pale Looks, Complaints, and Pains'.

Here, Behn reverses some of the keystones of contemporary polemic. One of the ironies of her endorsement of libertine freedom was that the concept of liberty was central to Whig political rhetoric. But Liberty for Whigs meant political and religious freedom: freedom from monarchical tyranny, and the freedom to practise dissenting religion rather than Anglicanism. By appropriating freedom as sexual liberty, she can be seen as offsetting the rhetorical strategies of her opponents. And where they had traditionally attacked Tory/Royalist culture as debauched and licentious, here it is the moral zealots, the guardians of 'Honour', who are said to be the 'base Debaucher of the generous heart'.

The Tory Cavalier

Behn's political philosophy centred around a celebration of the young elite male, the cavalier, the epitome of individual freedom. True freedom was freedom from want, from customary behaviour, and from religious fanaticism. In 1677 she located these qualities in the witty, genial, and womanising cavalier Willmore in The Rover, whom she revived in a sequel, The Second Part of the Rover, in 1681.

But as political tensions grew in London, her cavalier changed: in the early 1680s, the height of the Exclusion crisis, he become more predatory and manipulative, while at the same time retaining his wit, love for women, and royalism. This new sort of cavalier, more rake than rover, reappears as Loveless in The Roundheads(1681), and as the Tory, Tom Wilding, in The City Heiress(1682).

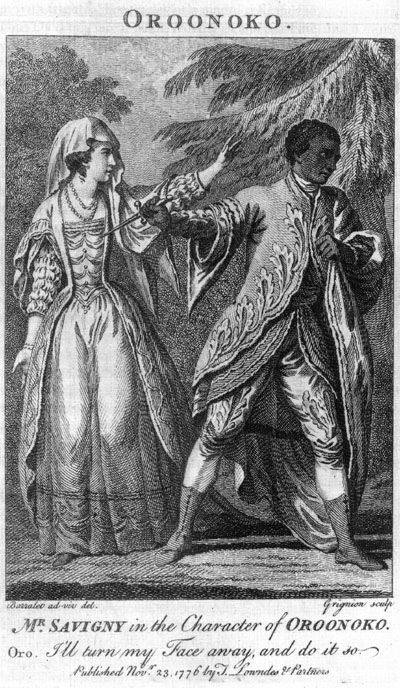

Things were to change again over the course of the decade, and by the late 1680s, when both the heady culture of Restoration libertinism and the Stuart monarchy that had typified it were in trouble, Behn concentrated on the tragic and romantic dimensions of the cavalier, in her portrayal of the 'royal slave' in Oroonoko, and the doomed warrior-hero, Nathaniel Bacon, in The Widow Ranter (1690).

For Behn, the cavalier's sword, noble birth, and code of honour were in danger of becoming meaningless in a world run by the crude and ambitious middling sorts who knew no loyalty to the monarchy, deference to birth, or respect for a man's word. The exceptional individual, unbound by custom, law, or religion, was lost in the clamouring demands of the multitudes, with their levelling politics, and mercantile interests.

Women were participants in the cavalier's drama, but were not themselves cavaliers. Behn was an extraordinary woman in many ways, and came as close to a she-rover as any woman could in her time. But she realised that the cavalier's libertine lifestyle was ultimately unobtainable for most women. Her witty heroines may engage in clever banter, and talk about how they despise the drudgery of marriage. But most often, they must marry or be ruined. In Behn's works, the opportunities for women of quality are pretty circumscribed.

An interesting perspective on the relationship between gender, party-affiliation, and cavalier culture can be seen in The Roundheads, one of Behn's most overtly political plays. The play is a comic satire on the last days of the Commonwealth, in which factionalism has resulted in political chaos, and the crown is contested by bribery, deception, and the sword. Behn uses the notion of a hierarchy inverted, where men are ruled by women, to show the extent of the topsy-turvy transgression against the public sphere. Women clearly have overstepped their bounds in The Roundheads, holding committee meetings, redressing petitions and advising men. Lady Lambert, the 'she-Politician', rules her husband, while Lord Lambert and the other Roundheads have usurped political power, and noble titles and estates. The heroic cavalier Loveless laments that he could once:

'…have boasted Birth and Fortune

Till these accursed times, which heaven confound,

Razing all our Nobility, all Virtue,

Has render’d me the rubbish of the world;

While new rais’d Rascals, canters, Robbers, Rebels,

Do lord it o’er the Free-born, Brave and Noble'.

The play ends with the royalist leader, General Monk, marching in on London. The Roundheads scatter, and Lord Lambert is arrested. The social and political order is restored, and significantly, in the final act of the play, Lady Lambert comes to her senses both about her gender and her politics. She is restored to her rightful place in society, no longer a meddling she-politician, but simply a woman in love. Loveless sighs:

Loveless: I love this Woman! Vain as she is, in spight of all her Fopperies of State— [bows to her and looks sad]

Lady Lambert: Alas, I do not merit thy Respect,

I'm fall'n to Scorn, to Pity and Contempt.

Ah Loveless, fly the Wretched—

Thy Vertue is too noble to be shin'd on

By any thing but rising Suns alone:

I'm a declining shade.

Loveless: By Heav'n, you were never great till now!

I never thought thee so much worth my Love,

My Knee, and Adoration, till this Minute.

— I come to offer you my Life, and all,

The little Fortune the rude Herd has left me.

Lady Lambert: Is there such god-like Vertue in your Sex?

Or rather, in your Party.

Curse on the Lies and Cheats of Conventicles,

That taught me first to think Heroicks Divels,

Blood-thirsty, lewd, tyrannick Savage Monsters.

But I believe 'em Angels all, if all like Loveless.

What heavenly thing then must the Master be,

Whose Servants are Divine?

So the true natural leader, the male cavalier, assumes his rightful place in a divinely ordered society. One of the essential characteristics of the cavalier is his reverence for truth, the code of honour, in which a man's word is his oath, a pledge of fidelity, trust, and loyalty. As we have seen, this was offset against the dissimulation of the Dissenters, who used 'cant' to deceive, smuggling in seditious politics under the guise of godly language.

In Oroonoko, published on the eve of the revolution of 1688, and at the end of the Restoration culture that Behn had so much celebrated in her earlier works, we see the plight of a man of his word who is out of his time. As a number of critics have shown, the depiction of the African prince, Oroonoko, is very much derived from the constructions of exotic nobility of Restoration heroic drama. These plays, like Dryden's The Indian Emperor, or Aureng-Zebe, tranferred contemporary debates about the nature of royal authority to far away scenes in the Americas, using Europeanised monarchs to celebrate the Stuarts' divinely sanctioned sway. Oroonoko is very much in this mode: he is thoroughly Europeanised, and his fate is not so much the fate of the black man, but of the monarch wrongfully enslaved. Like Behn's earlier cavaliers, he finds himself at sea in a world where an aristocratic code of honour has no place. He is continually tricked by whites who give him their word, and when he is lied to again after his failed slave rebellion, he concludes:

'He knew what he had to do, when he dealt with men of honour, but with them [false white men] a man ought to be eternally on his guard, and never to eat and drink with Christians without his weapon of defense in his hand, and for his own security, never credit one word they spoke'.

If Oroonoko was a coded warning to James II to watch who he too trusted, it failed. In 1688, shortly after the Queen gave birth to the male heir that would have secured a Catholic succession, a group of seven statesmen signed a letter of invitation to the staunchly Calvinist William of Orange, James's Dutch son in law, in which they offered him their support if he brought a force to England against James. William III landed at Torbay in Devon on 5th November. By the end of April 1689 William and Mary had been crowned king and queen of England, and five days after this, Behn died.

For Aphra Behn, the Williamite revolution represented the usurpation of the dynasty that she had spent her life writing in support of. Her poem to the Whiggish Anglican cleric Gilbert Burnet in many ways provides a fitting conclusion to her career as a political writer. The poem is a response to Gilbert Burnet, who had asked her to provide a panegyric on the accession, and it articulates Behn's unwillingness to back the Whig side. She explains her inability to join the celebration at the arrival of William, since:

'…loyalty commands with pious force,

That stops me in the thriving course,

The breeze that wafts the crowding nations o'er,

Leave me unpitied far behind

On the forsaken barren shore'.

Yet the poem also reveals her conviction of the writer's political agency, for better or for worse. She pays Burnet, the arch-propagandist, the double-edged compliment that it is his pen that has brought about the Revolution:

'Oh strange effect of a seraphic quill!

That can by unperceptable degrees

Change every notion, every principle,

To any form, its great dictator please'.

The poem it thus a tacit acknowledgement of the limits and the powers of the committed political writer. Behn's own career as Tory mythmaker was effectively finished by the Revolution, but the accession of William and Mary validated the potential of Burnet as propagandist. Behn's time might have come and gone, but, she suggests, the pen would continue to be mightier than the sword.

Complications to the Tory Behn

I've presented an account here that suggests that in Behn's writing we can see a coherent and sustained commitment to Tory politics. But one thing that complicates my account of Behn as Tory is her involvement in the MS verse miscellany, entitled 'Astrea's Booke for Sings and Satyrs', which is in the Bodleian Library. This is a collection of hand-written lampoons, written between 1685-88, and the entries are copied by several people, one of whom may be Behn. It looks like her writing, and on the front is written 'Behns and bacon'. The collection includes a number of satires and lampoons on the same public Tory figures that Behn celebrates elsewhere in her writings: there are scurrilous attacks on James II, Roger L'Estrange, and John Dryden.

The question is, what do we make of it? Does it suggest that she was politically two-faced, and that she was prepared to write Whig propaganda when it suited her, or that in the late 1680s she had become disenchanted with Tory politics? Or, as Todd suggests, was this another of her moneymaking projects? Behn had earlier picked up work as a copyist, employed to transcribe poems and manuscripts for various booksellers. Writing out lampoons was a thriving business in the 1670s and 80s, and in the later 80s Behn was suffering from the loss of revenue from the theatre. The fact that she may have been employed to copy the poems out doesn’t mean that she was necessarily committed to the politics in them.

But even if we accept that Astrea's Book was only the work of a copyist, Toryism was not an unproblematic position for Behn to adopt, or maintain. She did not come from the kind of background that she so idealised in her imaginative works. As the daughter of a wet-nurse and a barber, she was more trade than gentry, and would always, ultimately be outside the world of aristocratic ease for which she articulates such a nostalgia. Although she mocks the aspirations of women aping their betters, such as Isabella in The False Count, in many ways she shared with them the desire to attain to the leisured classes.

It is worth bearing in mind when thinking about Behn's articulation of her political philosophy just how far it represents an act of self-fashioning, the ventriloquising of a set of attitudes that could not have come naturally to her. Along with this, of course, comes the irony that as an independent, self-made woman, she should have chosen to adopt, and to articulate, a political ideology based around the figure of the young elite male, the cavalier. Some critics have argued that Toryism offered a very liberating basis for female independence, while others have stressed the extent to which its emphasis on conservative patriarchy sat uncomfortably with a proto-feminist agenda. It is impossible to know how Behn's politics conditioned her attitudes towards gender, since as yet we have no tradition of Whig women's poetry to compare it with. But it is safe to say that there is nothing straightforward about Aphra Behn as a Tory writer.

See also:

Who is Aphra Behn? - by Abigail Williams (ed. Kate O'Connor)

Aphra Behn and the Restoration Theatre - by Abigail Williams (ed. Kate O'Connor)

Aphra Behn and Poetic Culture - by Abigail Williams (ed. Kate O'Connor)