In 1908, Martha Pike Conant commented that:

"Historians of English fiction have insufficiently recognized the fact that the oriental tale was one of the forms of literature that gave to the reading public in Augustan England the element of plot which, to a certain extent, supplemented that of character." (a)

Subsequent histories remained, despite Conant's intervention, wedded to the exploration of the "Englishness" of the novel in Britain. While the influence of a small number of French and Spanish fictions (Marivaux's La Vie de Marianne (1731-42), Cervantes' Don Quixote (1605)) is acknowledged, the novel continues to be cast as an expression of national identity and especially the increasing dominance of empirical philosophy and mercantile values within the national culture. Ethnocentric accounts of the rise of the novel in England have seen it as a product of indigenous traditions (in news reporting, ballads, history writing) or at best an imitation of other European traditions (the Spanish/Italian novella or the French romances and nouvelles). (b) An honourable exception is found in the work of Margaret Anne Doody who argues for the importance of Greek and Roman classical fictions in shaping the modern novel in her True Story of the Novel (1998); she complains that the genre of the novel is an invention of English writing alone. (c) Although William B. Warner accurately diagnoses the history of the eighteenth-century novel as an ongoing struggle between the absorptive pleasures of reading and the mission to ensure that it provide a vehicle for the transmission of virtue, he nowhere considers the importance of the narrative frame of the Arabian Nights Entertainments (1704-1717) as a model in this struggle. (d)

In returning to a consideration of the contribution of "oriental" or "pseudo-oriental" sources to the development of the novel in Britain, we can also move beyond Conant's simple understanding of these texts as a rich source of plot, to a broader consideration of the way fiction came to be conceptualised in the period: as a kind of fabricated import, a hybrid construction similar to other commodities in demand and imported from the Orient in the period such as Indian muslin or Chinese porcelain. This is not to abandon the argument about the "national" character of the novel in Britain, but rather to recognise that it could be taken as a measure of the strength and adaptability of an emergent "Britishness" that it could speak from and of the place of the "other." Moreover, the influence of oriental narrative derives from its staging of the reading process as a form of imaginative "transmigration" on a number of different levels. First, oriental fiction consists of "shifting shapes" on the level of narrative content: Arabic djinns, lives of the Buddha, animals that become human and vice versa in Indian fable. Second, narrators and addressees in oriental fiction learn to inhabit different identities: the two most influential oriental fictions of the early eighteenth century, the Arabian Nights Entertainments and the Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy (1687-1694) are narrated by figures whose survival rests upon the continuing production of textual credit. Third, the European reader must engage in acts of transmigratory identification, projecting him or herself into the place of the eastern interlocutor. And finally, on the level of meta-narrative, oriental fiction is also a shape-shifter, undergoing powerful transformation when it migrates in diverse and numerous forms to a new continent in the eighteenth century, never wholly or entirely a fictional invention of the East by the West nor a colonising or observing traveler maintaining its "native" dress. (e) In other words, English readers of the oriental tale would hear the pun in the word 'fakir', the Arabic term for a poor man which came in the seventeenth century to refer to a Mahommedan religious mendicant and inaccurately to Hindu devotees and naked ascetics, as the idea of a 'faker', someone who fabricates an apparently magical scenario in order to gain textual, political and religious credit with a credulous public.

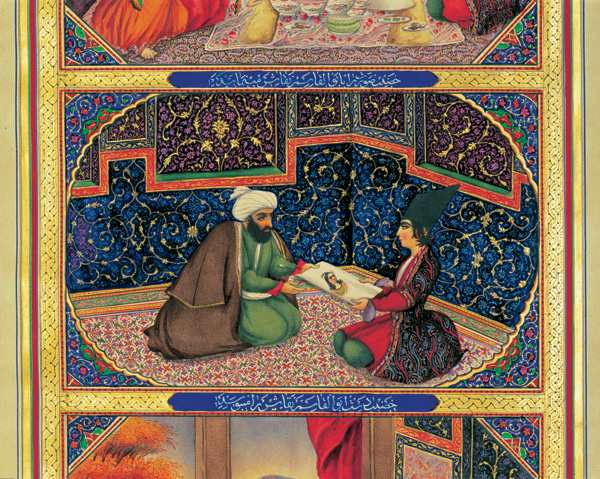

We cannot overestimate the influence on the development of British fiction of the twelve-volume "translation" by Antoine Galland of numerous tales drawn from a variety of Arabic sources, manuscript and oral. Galland's translation was overtaken in the nineteenth century and twentieth century by a more shocking translation (Sir Richard Burton's The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night of 1885-88) and later a more accurate one (Husain Haddawy's 1990 translation of the fourteenth-century Arabic manuscript which was Galland's principal source), but throughout the eighteenth century Galland's text went into multiple reprints (f) and generated countless imitations. This act of occidental ventriloquism, made significant contributions to the development of English fiction despite their diffuse and compendious character. What I concentrate on here is their metafictional awareness of the power of narrative, even when delivered from a subaltern position, to engage, direct and correct the imaginative sympathies of its consumer. Antoine Galland's Livre des Mille et une Nuit (1704-1717, translated into English c.1706-1721). Galland's volumes were translated one by one almost as soon as they appeared in France into small cheap octavo volumes known as 'the Grub Street translation' and available in a paperback version from Oxford University Press edited by Robert L. Mack for you to look at now. (g) It was then part of the burgeoning literary 'market' in cheap translation, even though Galland himself might be seen as part of a high-cultural precieuse salon narrative tradition in France. This history of the Nights in England suggests links between the idea of narrative as an accretive market-oriented phenomenon, directed toward the servicing of readerly pleasure inscribed within the Nights themselves (these stories originally circulated in the Orient as oral tales told in coffee-houses by traveling performers).

Dinarzade sleeps at the foot of her sister's marital bed and remembers to wake early each morning and request the continuance of the previous night's tale. The stories of the Arabian Nights Entertainments are thus framed as an exchange between women which is observed by a listening man, who is in fact their intended recipient. It is a frame that is repeated, manipulated, and parodied in eighteenth-century fiction in western Europe.

European reception of the oriental tale was always framed in terms of a claim for its potential as a vehicle for morality, but consistently revealed an enthusiasm for, indeed compulsive addiction to, narrative itself. Like Schahriar and the myopic despots who listen to so many of the sequences, readers find themselves 'blind' to the message and caught up in the pure pleasure of story-telling and its continuance. Indeed, the 'message' of the tale must necessarily remain veiled according to the logic of the sequence so that the auditor is insensibly led to mimic or imitate its 'truth'; too visible an intention would lead to the end of storytelling and retribution, since the despot is, by definition, not open to criticism.

As Muhsin Mahdi observes of his edition of the fourteenth-century Arabic manuscript in the Bibliotheque Nationale at Paris which formed the basis of Galland's 'translation' (but by no means the sum of the stories he included in the twelve French volumes) 'whoever examiines this edition with care and reads it from beginning to end finds no connection between all the stories in it other than the brittle thread woven by Shahrazad who narrates them, her sister Dinarzad who requests them, King Shahriyar who listens to them'. (h) Critics who write about the Nights have nevertheless traced relations between stories and between the frame narrative and enframed stories; Eva Sallis notes that the majority of stories in the collection share the concerns of the frame narrative: conflicts of power, between the sexes, themes of art and life and death. (i) Sallis prefers to see that resonance as a repetition of the theme of storytelling's power to defer violence and heal psychic rupture (in the disturbed despot Schariyar). Robert Irwin also notes that as we read we see resemblances and recurrence of patterns and combinations of character and action; he concludes that the 'Nights' may best be read as a narrative about the use of narrative as survival strategy. (j)

Mushsin Mahdi confirms this claim with respect to the three opening stories told by Scheherazade (The Fable of the Ass, the Ox and the Labourer, The History of the first Old Man and the Bitch, and The Story of the second Old Man and the two Black Dogs), each of which concerns the use of story as a form of ransom for an imperiled life' (vol. 1, p. 133). A recurrent structure is one in which a figure of power is persuaded or decides to hear a story with the promise that, if it 'satisfies' (even if only the craving for the pleasure of story itself), the speaker will be excused a proposed punishment. This structure organises the storygroup of 'The three Calenders, Sons of Kings; and of the five Ladies of Bagdad' in which three one-eyed calenders (mendicant monks) tell the stories of their mutilation to three ladies in order to avert the sentence of death passed upon them by the ladies for the transgression of an injunction against inquiring into the ladies' mysterious conduct; in turn, the three ladies 'explain' their behaviour to the listening/observing sultan (whose presence thus repeats the tri-partite frame structure of the 'Nights' of story-teller, listener and the addressee who 'overhears'). And the same structure is repeated in the inset stories to 'The Story of the little Hunch-back' in which a Christian merchant, a purveyor, a Jewish physician, and a tailor tell stories in order to have the sentence of death passed by the caliph on the merchant for the supposed 'murder' of the little hunch-back remitted; their stories must prove to be more extraordinary than that of the 'death' of the hunchback whose body each of the tellers has encountered and disposed of surreptitiously. The tailor provides another inset story of a garrulous barber who has told him about the misfortunes afflicting his six brothers; then the barber himself appears and restores the hunchback to life.

Thus the juridical sentence can be overtaken or overcome by the narrative sentence; indeed the latter conjures the presence of the healing barber himself. Story is thus a form of agency in the Arabian Nights Entertainments, bringing about metamorphosis, especially the most profound metamorphosis of all, from death to life or vice versa. On one level, we can read the stories as parables about the role of fate in individual existence. Predestination is a central tenet of Sunni Islam and the stories of the Nights frequently demonstrate that the attempt to avoid fate only leads to it. Thus, in 'The History of the third Calender', prince Agib is shipwrecked on an island where he meets a boy who has been immured in an underground cave by his father to avert a prophecy that he will be killed within forty days by the prince Agib; Agib befriends him but when reaching for a knife to pare a melon accidentally stabs him to death. Fate is then a story which cannot help but be fulfilled; fate stands for the storyteller (see Irwin, p.197). To some extent this is Scheherazade's role; as Mahdi notes she tells of past events as a means of foretelling future events and happy endings, returning her monarch husband to the path of virtue in a parable of revealed religion correcting the errors of a transgressive heathen royalty (pp.127-30). However, Scheherazade might also be seen as an active averter of an unjust decree, correcting her husband's claim to act as a surrogate 'fate' who exercises a false authority in the name of the divine. The stories by no means advocate quietism and submission to a prescripted destiny; characters such as Sinbad are praised for their enterprising and individualistic action.

Thus, the merchant hero and the seraglio heroine are linked through their strenuous attempts to turn narrative destiny into profit and credit, Sinbad in terms of material gain and Scheherazade in terms of symbolic capital. However, as so often in the oriental tale, the symbolic capital accrued by women's story-telling activity does not always attach to women in general and Scheherazade's tale-telling tends to prove her eccentricity rather than her exemplarity in relation to other women. Take, for example the narrative fortunes of another witty female favourite who exercises narrative authority, Zobeide, favoured wife of the Caliph Haroun Alraschid. We first encounter Zobeide as the mistress of an all-female household who directs the pleasures and story-telling activities of the three calenders and a porter at the home she shares with her sisters, Amine and Safie. The caliph, his vizier Giafer and the chief of his eunuchs Mesrour, stumble upon the festive household on one of their incognito late-night rambles through Bagdad, but all the men fall under sentence of death from the sisters when they break the promise they made not to enquire into the ladies' strange behaviour: the weeping women whip two bitches in the company's presence and Amine bears strange scars on her neck. Zobeide promises to remit the sentence if the men tell their own stories to the ladies, is satisfied with their performance and releases them; the next morning the caliph summons the women to have them explain their conduct.

Zobeide reveals that the bitches are her two full sisters who have been turned into dogs by a fairy to whom she had done a service as a punishment for throwing Zobeide and her betrothed into the sea in a fit of jealousy, resulting in the latter's death. The fairy orders her to whip them without fail each night. Amine's scars have been inflicted by her jealous husband for exposing her face to another man. He is revealed to be the caliph's son Amin. The fairy is recalled and is persuaded to transform the dogs back into humans and heal Amine's scars at the behest of the caliph and the caliph marries Zobeide while the other three sisters marry the one-eyed calenders. At this stage then, Zobeide's role mirrors that of her narrator, a woman who wins the love of the sultan through her beauty and her wisdom and whose cryptic surface conceals a secret knowledge and purpose. She facilitates the meeting of men and women in women's quarters to enjoy each others company free of the usual restrictions of speech and vision and, indeed, controls what can be seen and heard in that space, rather than being subject to the control of eunuchs or the despotic gaze of the ruler. She appears briefly in 'the Story told by the Sultan of Casgar's Purveyor', once more in the form of a sympathetic ameliorator of the restrictions on heterosexual romance in the confined space of the seraglio; she recognises the secret love between a young nobleman and one of her ladies and permits them to marry.

However, Zobeide's licence itself turns into despotism by time we reach 'The History of Ganem'. The son of a merchant observes some slaves secretly burying a chest, and retrieves from it the drugged body of a woman. He revives her and discovers she is Fetnah, rival for the caliph's affections, whom Zobeide has drugged and arranged to be buried alive. Fetnah lives secretly with Ganem and Zobeide informs Haroun Alraschid that she died in his absence. Ganem's family suffer severe persecutions when the caliph discovers Fetnah is alive and it is only after much suffering that his innocence is proved, Zobeide cast off and the caliph marries his virtuous sister and the vizier his equally virtuous widowed mother. When Ganem returns to Baghdad he finds his relations thus exalted and can marry Fetnah.

It could be argued that the Nights is simply a catchall collection of stories and readers are not expected to associate the Zobeide with one story with the Zobeide of another. Stories certainly do not figure in chronological sequence and they derive from different parts of the east and from different historical moments. Certainly, Zobeide reappears a few stories later in a humorous story called 'the Sleeper Awakened' in which the sultan's favourite Abon Hassan and his wife, Zobeide's ex-slave Nouz-ha-toul-aonadat, trick Zobeide and her husband into giving them gifts to support them in their supposed grief at the death of a spouse; when the cheat is discovered, Zobeide and Haroun Alraschid are entertained rather than offended. However, similar reversals, especially in the characters of women, happen within single stories such as that of Badoura, Princess of China who is married to her physical and spiritual 'twin' Prince Camaralzaran of Khaledan, heroically sets off in search of him in male disguise when they are separated, advances to the role of vizier at Ebene and persuades Camaralzaran, when he reappears to marry her 'wife', the princess, only to fall criminally in love with her stepson (by the princess and Camaralzaran) and then accuse him of attempted rape when he rejects her advances. Princess Haiatalnefous, her fellow wife, acts in the same way toward Badour's son. Their perfidy is not discovered until after the two young men have been reported to be executed, and Camaralzaran orders both women confined to prison for the rest of their days. After many adventures which prove their virtue and their exemplary Muslim behaviour in their encounters with idolaters the two sons are reunited with their father.

Such reversals in character are, of course, common to long narrative and primarily oral sequences, familiar to modern readers from soap opera; a character can transform over a long period of narrative time from hero to villain and vice versa. However, they are largely confined to the female characters of the Nights and could also be seen to point to the ambivalence of the position of the loquacious politically-active woman in the oriental tale.

Silence is the only guarantor of female virtue in the tales; thus in 'The Story of Beder, Prince of Persia', the prince's mother is acquired as a slave by his father but refuses to speak until she is pregnant when she reveals her real identity as a princess of the sea and becomes the queen-consort to her newly monogamous husband. The queen Gulnare acts to protect her son at various points in his story; he falls prey to the magical powers of two women, the princess of Samandal (another watery kingdom) who is so offended when he declares his love that she turns him into a bird and the Queen of Labe who turns him into an owl as she has done all the other men she has taken to her court as favourites. It is Gulnare, his mother, who transforms him back into human form from this last metamorphosis. As Diderot's parody suggests, the open female mouth is always a possible indicator of a sexual 'openness' which threatens the enclosure and ownership of the seraglio woman.

Why then does Scheherazade narrate stories which appear to threaten her own position, and point to the possibility of the potential unchastity she shares with all women? Again, it could be argued that this is to thematise a loose collection of tales from different cultures, sources and contexts - folk-tale, state history, fairy tale, court intrigue - and to invest the frame as determining the nature of all the narratives it encloses (rather as the sultan does all women, extrapolating a universal tendency from a few instances). Galland put together his materials from a variety of sources and a number, often the best known such as the Sinbad sequence and Aladdin, are not found in his Arabic souce which gave him the frame structure. However, he did also seek to give the frame some prominence, to the extent of inventing a conclusion which resolved Scheherazade's tale, and there can be little doubt that eighteenth-century readers understood and remembered the Nights as a framed sequence rather than simply a 'storehouse' for story.

Galland's conclusion points to a way of understanding Scheherazade's risky strategy of inscribing an ambivalence about female speech into her own speech:

The Sultan of the Indies could not but admire the prodigious memory of the sultaness his wife, who had entertained and diverted him so many nights, with such new and aggreable stories, that he believed her stock inexhaustible.

A thousand and one nights had passed away in these agreeable and innocent amusements; which contributed so much towards removing the sultan's fatal prejudice against all women, and sweetening the violence of his temper, that he conceived a great esteem for the sultaness Scheherazade; and was convinced of her merit and great wisdom, and remembered with what courage she exposed herself voluntarily to be his wife, knowing the fatal destiny of the many sultanesses before her.

These considerations, and the many rare qualities he knew her to be mistress of, induced him at last to forgive her. I see, lovely Scheherazade, said he, that you can never be at a loss for these sorts of stories to divert me; therefore I renounce in your favour the cruel law I had imposed on myself; and I will have you to be looked upon as the deliverer of the many damsels I had resolved to have sacrificed to my unjust resentment.

The sultaness cast herself at his feet, and embraced them with the marks of a most lively and sincere acknowledgement. (Mack, .892)

Both the motive behind and the nature of Schariar's decision are purposefully confused here, suggesting that perhaps the one lesson learned from his consumption of so many tales is the agency of ambivalent statement. When we are told that he has chosen to 'forgive her' we must necessarily ask what crime it is that he forgives; the crime of all women, of unchastity, which has not in any case been proved against her or the crime of speaking out in his presence, of daring to 'teach' an absolute ruler and question the absoluteness of his decisions? Moreover, the reason for his reversal of intention (the decision to 'forgive') is not clear. He nowhere suggests that the stories themselves have proved the possibility of female virtue. It is the fact that they amuse and divert him, rather than returning him to the obsessive jealousy which had preoccupied his thoughts before the sequence commenced, which have 'contributed so much towards removing the sultan's fatal prejudice against all women'. How can one woman telling many stories prove to the listener that all women are not unchaste? What they have proved is that their teller is clever, entertaining and a fit, if not superior, intellectual companion.

Indeed, Scheherazade's greatest success as story-teller may be in her delivery of stories which have nothing to do with 'proving' or 'disproving' female virtue. Sinbad's voyages, for instance, like Robinson Crusoe's adventures, prove the resilience of the protagonist while his fortune magically accrues without much positive action on his part. 'The Story of Cogia Hassan Alhabbal' in which the rope-maker loses a vast fortune given to him by the rich Saadi but succeeds in turning a vast profit from a simple bar of lead given by the poor Saad demonstrates the same magical power of profit without intention. Scheherazade's stories similarly appear to succeed by their circulation alone; their producer need not husband or manage her resources particularly, but rather simply keep them in circulation and her symbolic capital magically grows.

This may be why the Nights remained from their first appearance onwards the touchstone and paradigm of the oriental tale, the sequence ever burgeoning and expanding, but always retaining its magical power as sign of the east for its western readers. The Nights, like the woman who tells them, transform the world around them by repetitive acts of simple accretion. It is not what they tell that matters so much as the stubborn vitality of their matter itself, which continues to survive and grow requiring only assent to their continuance rather than complex acts of interpretation or organisation on the part of their auditor(s). In this, the Nightschime with and indeed confirmed common prejudices about eastern cultures expressed in travel and historical accounts throughout the early modern period: that eastern nations can only imitate rather than originate genuine art, that eastern economies accrete wealth at the centre and fail to turn the circulation of wealth into genuine commerce and trade between nations. Above all, the east is understood as not only a place of fiction, indeed a fictional place, in so far as it only appropriates, transforms and mimics as simulacra, or copy without original, the east is also imagined as feminine and feminised, a weak and derivative copy of the male according to early modern theories of sex, and here too, the Nights both imitates and confirms the myth in its deployment of a female story-teller as framing device. However, the feminine imitator/mimic also generates copies in her image, not only in the shape of the male Orientalists who 'translate' her and find themselves 'translated' into the position of feminised imitator without a claim to originating genius, but also within the narratives themselves.

Notes:

- Martha Pike Conant, The Oriental Tale in England in the Eighteenth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1908), 242.

- For the former see Lennard Davis, Factual Fictions: the Origins of the English Novel (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983) and Robert Mayer, History and the Early English Novel: Matters of Fact from Bacon to Defoe, Cambridge studies in eighteenth-century English literature and thought ; 33 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). For the latter see Ros Ballaster, Seductive Forms: Women's Amatory Fiction from 1684 to 1740 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992).

- Margaret Anne Doody, The True Story of the Novel (London: Harper Collins, 1997), 1-2.

- William B. Warner, Licensing Entertainment. The Elevation of Novel Reading in Britain, 1684-1750 (London and Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998).

- Oriental sources had been translated and considered in earlier periods, of course, especially in the middle ages as a consequence of the encounter with Islam through the Crusades, but never on the scale and in the variety seen in this period and, largely, initiated, by Galland's voluminous translation. For earlier instances, see Dorothy Metlizki, The Matter of Araby in Medieval England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977).

- The Arabian Nights Entertainments went into nineteen editions by 1798 and the Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy went into fifteen editions by 1801 (the last edition of all eight volumes complete).

- Robert Mack ed. , Arabian Nights Entertainments (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

- Muhsin Mahdi, Alf Layla wa Layla , 3 vols. (Leiden: Brill, 1984), vol. 1, p. 140.

- Eva Sallis, Sheherazade Through the Looking Glass: The Metamorphosis of the 'Thousand and One Nights', Routledge studies in Arabic and Middle-Eastern literatures (London: Taylor and Francis, 2011), p.83.

- Robert Irwin, The Arabian Nights: A Companion (London: Allen Lane, 1994), p.215, p.236.