King Alfred the Great (c. 849–899) is one of the most important figures in English history and one of the first named English writers. When he came to the throne of Wessex in 871, almost all of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were under Viking rule. By the time of his death in 899, Alfred had defeated the Vikings in the south and forged a new kingdom by uniting the West Saxons with the Anglian-speaking Mercians to the north. In the midst of these turbulent political events, Alfred still found time to devote himself to learning Latin and producing books in Englisc (‘English’), the language of his subjects the Angel-cynn (‘race of the English’). We now call the language of King Alfred’s day Old English, to distinguish it from Middle English, the language of Chaucer, and Early Modern English, the language of Shakespeare. Although it may not look much like English to us, the closer we look the more we start to see how the Englisc spoken in the late ninth century is a direct ancestor of the language we speak now. It was under Alfred’s successors in the tenth and eleventh centuries that the kingdom of Engla-lond took shape, as West Saxon rulers extended their power further North and East. Many more books were produced in Old English during the post-Alfredian period, including the writings of contemporary churchmen such as Ælfric, who developed his own distinctive alliterative prose style. We also have this period to thank for the only surviving copies of Old English poems such as Beowulf, The Wanderer and The Dream of the Rood. Without Alfred, however, the English language itself might not have survived the Viking age.

In the words of his Welsh biographer, Bishop Asser, Alfred was a pious youth who loved ‘reading aloud from books in English and above all learning English poems by heart’. In order to meet his desire for wisdom, Alfred sought out the best scholars from across Europe. These men brought with them Latin books that could be discussed at court and translated into English. According to the Anglo-Norman historian William of Malmesbury, Alfred ‘translated into English the greater part of the Roman authors, bringing off the noblest spoil of foreign intercourse for the use of his subjects’. William lists among Alfred’s translations works by Gregory the Great, Orosius, Boethius and Bede, and says that he was working on an English rendering of the Book of Psalms when he died. In several of the surviving manuscripts, prefaces and epilogues attribute the act of translation to the king himself. For example, a preface attached to the Old English translation of Boethius begins: Ælfred kuning wæs wealhstod ðisse bec and hie of boclædene on Englisc wende swa hio nu is gedon (‘King Alfred was the translator of this book and he translated it from book-Latin into English as it is now presented’). Scholars now debate the extent to which Alfred was personally involved in these translations—it seems likely that at least some of this work was carried out by scholars serving under Alfred’s patronage, or even during the reigns of his immediate successors, Edward the Elder (r. 899–924) and Athelstan (r. 924–939). But there can be no doubt that Alfred was the instigator of a series of important translations that had a transformative impact on English literature and culture.

In a letter sent by Alfred to his bishops in the 890s, the king laments the poor state of learning among the Angel-cynn, complaining that very few people can even read books in English nowadays, let alone Latin. In Alfred’s view, this shameful neglect of wisdom has contributed to the downfall of the English people:

Geðenc hwelc witu us ða becomon for ðisse worulde, ða ða we hit nohwæðer ne selfe ne lufodon ne eac oðrum monnum ne lefdon

(‘Remember what punishments befell us in this world when we ourselves did not cherish learning nor transmit it to other men.’)

In order to revive the fortunes of the Angel-cynn and restore them to God’s favour, Alfred proposes, with the help of his advisors, to have translated into English certain Latin books ðe niedbeðearfosta sien eallum monnum to wiotonne (‘that are most needful for all men to know’). The first of these books is Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care, a handbook for bishops that instructs them how to be a good pastor (‘teacher’) and rector (‘ruler’). It was Pope Gregory who had sent Augustine of Rome to Britain in 597 to convert the Angli (‘English’). Gregory’s book also had special meaning for the West Saxon king, who saw himself as not only as a war-leader but also as a spiritual protector of his people; in Alfred’s words, kings who obey God succeed ge mid wige ge mid wisdome (‘both in war and in wisdom’).

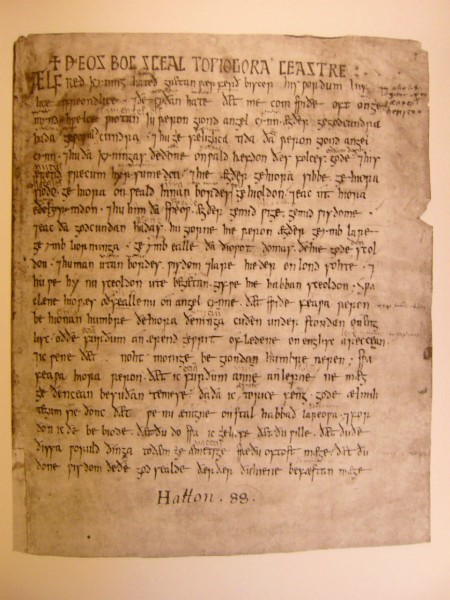

Preface to the Old English Pastoral Care (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Hatton 20)

Accompanying each copy of the Old English Pastoral Care was an æstel, an object which is identified with the Alfred Jewel, now kept in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

The Alfred Jewel (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

This tiny golden object, with a crystal inset above a serpent’s head, might originally have been used to hold a pointer for reading the book. Around its edges there is an inscription that reads:

ÆLFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN

(‘Alfred ordered me to be made’).

The iconography of the Jewel invites us to think of Alfred as an English Solomon, a ruler whose extravagant wealth is matched by his love of wisdom.

The Old English translation of the Pastoral Care itself, which the Jewel probably accompanied, is relatively conservative, sticking closely to the Latin, hwilum word be worde, hwilum angit of andgiete (‘sometimes word for word, sometimes sense for sense’). But in subsequent Alfredian translations, notably the Old English versions of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy and St Augustine’s Soliloquies, we start to see the emergence of a confident new English prose style. As well as frequently editing, rearranging and expanding on their Latin sources for the sake of clarity and accessibility, the Alfredian translators sometimes introduce their own metaphors, using familiar images to bring these challenging works to life in the minds of their English readers. For example, in the Old English version of Boethius the tricky subject of the relationship between divine providence and earthly fate is explained through the analogy of a wagon-wheel:

Eall ðios unstille gesceaft and þeos hwearfiende hwearfoð on þam stillan Gode and on þam anfealdan, and he welt eallra gesceafta [...] swa swa on wænes eaxe hwearfað þa hweol and sio eax stent stille and byrð þeah ealne þone wæn and welt ealles þæs færeldes.

(‘All this moving and turning creation revolves around the still and stable and single God, and he rules all creatures [...] just as the wheels turn on the axle of a cart and the axle stands still and yet carries all the cart and controls all the movement.’)

In the preface to the Old English version of St Augustine of Hippo’s Soliloquies, we find the author—identified at the end of the text as Alfred—travelling to the woods to gather timbers and other building materials, and advising others to do the same þat he mage windan manigne smicerne wah, and manig ænlic hus settan, and fegerne tun timbrian (‘so that he may weave many elegant walls and put up many splendid houses and so build a fine homestead’). On one level, Alfred appears to be encouraging others to follow his example in creating new structures—texts—out of old materials, namely the works of the Church Fathers. But Alfred is also building an earthly cotlyf (‘cottage’) as a place to dwell during this transitory life in preparation for the eternal home of heaven.

For Alfred and his circle of scholars, the precious wisdom contained in these books could easily be wasted if it was not made widely available in a language that people could understand: Englisc. Not only their lives but their souls depended on it. In a short poem which serves as an epilogue to the Old English Pastoral Care, the reader of the book is reminded that this text itself is wisdomes stream (‘wisdom’s stream’) flowing from God:

Gif her ðegna hwelc ðyrelne kylle

brohte to ðys burnan, bete hine georne,

ðy læs he forsceade scirost wætra,

oððe him lifes drync forloren weorðe.

(‘If any man has brought here a leaky pitcher

to this stream, let him repair it speedily,

so that he may avoid spilling the clearest of waters

or losing the drink of life.’)

Having witnessed the near destruction of his realm at the hands of the Vikings, Alfred knew all too well the precarious nature of royal power. But as a scholar, he also prized the wisdom contained in books and feared the terrible consequences of its neglect. To Alfred’s mind, the best way to ensure the continual flow of wisdomes stream to the English was to translate texts from Latin on ðæt geðiode ða we ealle gecnawan mægen (‘into that language so that we all might know them’). It was for this reason, as much as his military victories over the Vikings, that Alfred came to be known centuries later as ‘Alfred the Great’. In the words of the twelfth century poem, The Proverbs of Alfred: He wes king and he wes clerek (‘He was king and he was a scholar’).