Tracy K. Smith - Artefacts of Writing

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal

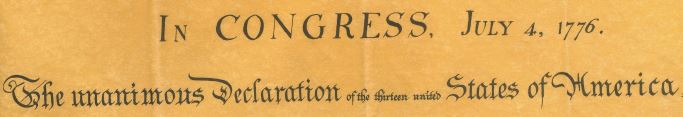

1. Who owns these words? If you mean ownership in a strict legal sense — for example, in the way the entity identified as Donald J. Trump for President, Inc [1]. owns the phrase ‘Make America Great Again [2]‘ — then the answer is no one. The words come from A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled, now commonly known as the US Declaration of Independence [3], which the Congress of the 13 American colonies ratified on 4 July 1776. It has long — arguably always — been in the public domain. Ownership in a looser sense could, then, be said to lie with Congress, or with the 56 original signatories, the most famous of whom — Thomas Jefferson [4], John Adams [5], and Benjamin Franklin [6] — also played a central part in the drafting. Most of the 83 words you are looking at here come from the third section, which lists the indictments against George III [7] who was then King of Great Britain and King of Ireland — he was still sovereign when the two countries formed the United Kingdom in 1801.

1.1. As the ‘long s [8]‘ in the second line above indicates — ‘ʃwarms’ and ‘harraʃs’ — the extracts come from the engraved copy of the original parchment which the printer William J. Stone produced in 1823. Though still common in the late-eighteenth century, the use of the ‘long s’ had begun to decline by the early years of the nineteenth.

Scene of the signing on the reverse side of US two dollar bill since the bicentenary in 1976

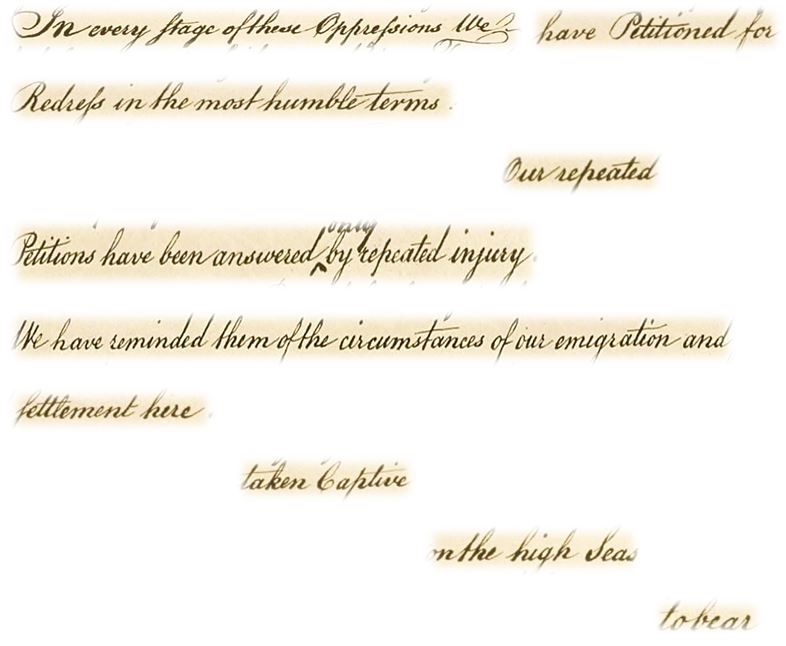

2. Flash forward 242 years and a very different answer to the question of ownership becomes possible. Now the same words appear in Wade in the Water [9], a collection of poems published by Graywolf Press in the United States and Penguin Books in Great Britain, both of which carry on their inside page the words ‘Copyright © Tracy K. Smith [10], 2018.’ With two exceptions — Smith dropped the ‘long s’ and modernized the spelling of ‘harass’ — the words appear in the same form too: capitalized ‘Officers’, for instance, and ‘high Seas.’ The difference is that they now comprise the body of a poem entitled ‘Declaration [11]‘, the first in a related sequence of five that make up section II of the four-part volume. Besides breaking and reordering elements of the prose original into 17-line free verse poem, Smith also produced the entire text in italics, a graphic device generally signalling quoted material in her books.

2.1 Given the many political, literary, and other questions the poem opens up, a further detail on the inside page of the US edition is worth noting. ‘This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota Arts Board [12] Operating Support grant,’ Graywolf [13] notes, ‘thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and the Wells Fargo Foundation [14].’ A corporate-sponsored organisation founded in 1979 and based like Graywolf in Minneapolis, Wells Fargo has a particular commitment to promoting diversity and social inclusion. Graywolf also notes the support provided by Target [15], the McKnight Foundation [16], the Lannan Foundation [17], and the Amazon Literary Partnership [18]. Though public bodies and private corporations help to keep poetry publication alive in Britain too — Carcanet [19], for instance, receives regular grants from Arts Council, England [20] — the British edition is a wholly commercial venture by the multinational Penguin Random House UK [21]. ‘Declaration’ first appeared unitalicized in The New Yorker [22] for 6 November 2017, 32-33.

3. The notes at the back of Wade in the Water describe ‘Declaration’ as ‘an erasure [23] poem drawn from the text of the Declaration of Independence’ (75). This makes it an instance of found poetry, the literary equivalent of collage art or the Dadaist’s readymade: poetry created out of existing textual artefacts, which are then recycled for new purposes, contexts, and readers. This practice could be said to include creative translation, considering, say, what the contemporary Indian poet Arvind Krishna Mehrotra [24] does with the medieval bhakti [25] poet Kabir [26] (see chapter 7 of the book, and Songs of Kabir [27]). More standardly, however, it is identified with work like the Afrikaans poet Antjie Krog’s [28] volume Lady Anne [29] (1989), which, among other source documents, refashions the letters and journals the Scottish colonialist Lady Anne Barnard [30] wrote while staying in the Cape in the late-eighteenth century (see chapter 6 of the book). Smith adopts the same practice, though to different ends, in ‘I Will Tell You the Truth about This, I Will Tell You All about It’, the penultimate poem in section II of Wade which, as the notes indicate, is ‘composed entirely of letters and statements of African Americans in the Civil War, and those of their wives, widows, parents, and children’ (75). ‘Declaration’ is certainly in this tradition, but, given its particular source text, methods, and preoccupations, it might be better thought of as a new sub-genre of found poetry: the expropriation poem.

expropriation.

d. The action of taking (property) out of the owner’s hands (esp. by public authority); an instance of this. (OED)

4. Erasure-effects, or verbal ghostings, undoubtedly contribute to the poem’s power and appeal. Marked by the dashes Smith adds to the source text, which underscore the verbal elisions and the spatial gaps created by the line breaks, these are particularly evident in lines 3 to 8:

He has plundered our — seas

ravaged our — coasts

destroyed the lives of our — people

taking away our — Charters

abolishing our most valuable — Laws

and altering fundamentally the Forms of our — Governments (17)

Smith’s suspended syntax leaves readers free to fill in the blanks as they see fit, reconstructing the indictment on their own terms.

5. Yet it is her handling of the inherent uncertainties of deixis [31], evident in the way her version re-contextualizes the pronouns (‘he’, ‘we’, ‘them’, and ‘our’), that opens up the creative possibilities of expropriation. For the framers of the original Declaration, the ‘he’ meant one person — George III — and the first-person plural forms were no doubt equally clear: they were writing as ‘We…the Representatives of the united States of America’, speaking on behalf of ‘our fellow Citizens’, and ‘in the Name, and by the Authority of the good People of these Colonies’. In Smith’s version, all the pronouns are radically dislocated and reclaimed for new purposes. In her hands, for instance, the ‘he’ becomes much less specific, more open-ended. It could be Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the original document, the 56 white, male signatories, or the all-white, all-male Congress, to think only of the historical possibilities. A more generalized oppressive ‘he’ is also conceivable. By contrast, read in the context of section II of Wade in the Water, which focuses on the African-American experience of the Civil War and addresses the history of slavery, the collective ‘we’ and ‘our’ become much more specific — consider the line ‘We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here’, which runs on to ‘– taken Captive / on the high Seas’. Since the title Wade in the Water comes from an African-American spiritual, [32] the collection as a whole supports this reframing. Given that the ‘fellow Citizens’ and ‘good People’ of the original Declaration did not include African Americans, indentured servants, or women, this particular act of creative expropriation has an especially powerful resonance.

5.1. Like most major, collectively-authored public documents — laws, charters, treaties, constitutions, etc. — the Declaration of Independence was itself an artefact of erasure. Most notoriously, Jefferson’s original draft included a passage [33] indicting George III for maintaining the ‘execrable commerce’ of slavery, which Jefferson described as ‘an assemblage of horrors’, but this was deleted as the draft made its way through Congress, an act of erasure that produced one of the greatest ‘what ifs’ of American history. This detail of its textual history adds further weight to Smith’s counter indictment, particularly if you read the ‘he’ as Jefferson who, for all his revulsion at the trade, remained a lifelong slave owner himself. By contrast, the final charge against the King, which includes a veiled reference to slave rebellions [34], did survive the drafting process: ‘He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.’

6. Smith has experimented with the creative possibilities of recycling public documents (and of deixis) since the beginning of her career. The poem ‘History’ from her second collection Duende [35] (2007), for instance, has a fourth section entitled ‘Grammar’, which begins:

There is a We in this poem

To which everyone belongs.

As in: We the People [36] –

In order to form a more perfect Union — (10)

The title Duende itself signals her preoccupation with the quandaries of ownership: meaning ‘elf’ in Spanish, a ‘duende [37]‘ is a mischievous folkloric spirit who takes possession of a house. By expropriating official documents and reworking them for her own poetic ends, Smith extends a rich tradition of literary duende-ism, which, as I show in Artefacts of Writing [38], ranges from James Joyce [39], who takes on the preamble to the Irish Constitution [40] in Finnegans Wake [41] (1939, see pp. 143-46 of the book), to Amit Chaudhuri [42], who engages with the Indian Constitution [43] in Odysseus Abroad [44] (2014, see pp. 252-60). As Joyce’s throwaway comment about the significance of 4 July in the United States indicates — he referred to it in a letter as ‘Independence, Dependence, Interdependence Day’ — his own doubts about the constitutional language of the modern state were not limited to Ireland.