Ben Jonson: Renaissance Playwright, Renaissance Man

Ben Jonson 1572-1637) was an early modern playwright whose popularity rivaled that of Shakespeare or Marlowe. He spent multiple stints in prison, wrote masques in which the Queen of England and Prince of Wales performed, and was crowned England's first poet laureate.

Yet for all this in 1572 he was born into relative poverty. His father died shortly before his birth, and his mother remarried a bricklayer. Luckily for the clever young boy, an unidentified friend paid for Jonson to attend Westminster School. After leaving school Jonson attempted to join his stepfather as a bricklayer, but the profession didn't take; legend has it young Ben recited Homer while building the walls of Lincoln Inn. In the 1590s Jonson served in the armed forces in the Low Countries, and in November 1594 Jonson married a woman he described as "a shrew, yet honest."

It's not certain when Jonson entered the theatre, but by 1597 he was an actor for the Admiral's Men. It was also in this year that his earliest surviving play, The Case is Altered [1], was performed by Pembroke's Company.

Too Witty for his Own Good

Jonson's sharp tongue got him into no end of trouble: In summer of 1597 the satirical comedy The Isle of Dogs, which Jonson co-wrote with Thomas Nashe, was performed, and the play upset the powers that be. Jonson was arrested along with two other actors, and the play may have prompted the Privy Council's order to close the London theatres because of "lewd matters that are handled on the stages, and by resorte and confluence of bad people."

Jonson was released within a few months, and apparently hadn't learned his lesson. In the summer of 1604 the Children of her Majesty's Revels performed Jonson's Eastward Ho!, a collaboration with George Chapman and John Marston. Eastward Ho! was a response to John Webster's [3] and Thomas Dekker's [4] Northward Ho!, and a salacious one at that. The play mocked King James, the Scots, knights of the realm, and courtiers, and all three playwrights were imprisoned until October.

On a less political note, Jonson was engaged in the "War of the Theatres", or "Poetomachia" between 1599 and 1602, in which Ben Jonson battled John Marston and Thomas Dekker by satirizing one another in their plays and poetry.

In the early to mid 17th century Jonson really hit his stride, writing such classic plays as Volpone [5] (1605), The Alchemist (1610), Bartholomew Fair [6] (1614), and The Devil is an Ass (1616). Even when he didn't cast thinly veiled aspersions on political figures, Jonson specialised in depicting witty banter, confidence tricksters, and devils in disguise of all sorts.

Courting the Court

Jonson was a man who liked his luxuries. Having been raised in poverty, he appreciated good food and creature comforts. He was a portly man apt to praise the finer things in his countless poems, and sought recognition from the court of King James I. He wrote more than twenty masques for the court, including The Masque of Blackness, in which Queen Anne herself performed. In 1616 Jonson was named England's first ever Poet Laureate.

Important and Self-Important Playwright

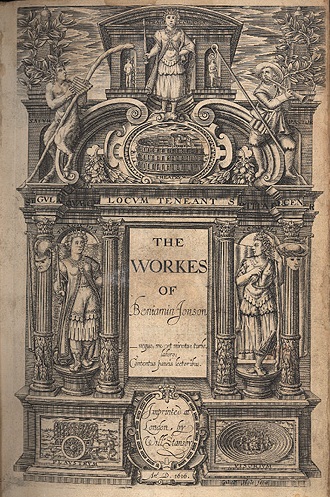

Jonson was aware of his legacy to a degree unprecedented among early modern playwrights. He was the first playwright to ensure his own works were published as a formal folio, treating his plays as works of literary note rather than as frivolous stage plays. The 1616 folio divided his works into plays, poetry, masques, and entertainments. The engraving on the title page went to great pains to associate Jonson with Greek scholars of old.

And perhaps that association was not unjust: Jonson was witty, intelligent, well read, and as capable a poet as he was a playwright.

"On My First Sonne", an elegy written after the death of his seven-year-old son Benjamin, is truly heartbreaking. Jonson was a true Renaissance man. The "Tribe of Ben" grew up from the 1620s, a group of poets who proclaimed themselves influenced by and successors of Jonson, included Robert Herrick and Richard Lovelace. Jonson suffered a series of strokes, fell out of court favour, and died on 6 August 1637.

Not a little because of his having ensured their publication, Jonson's works endure.